Description

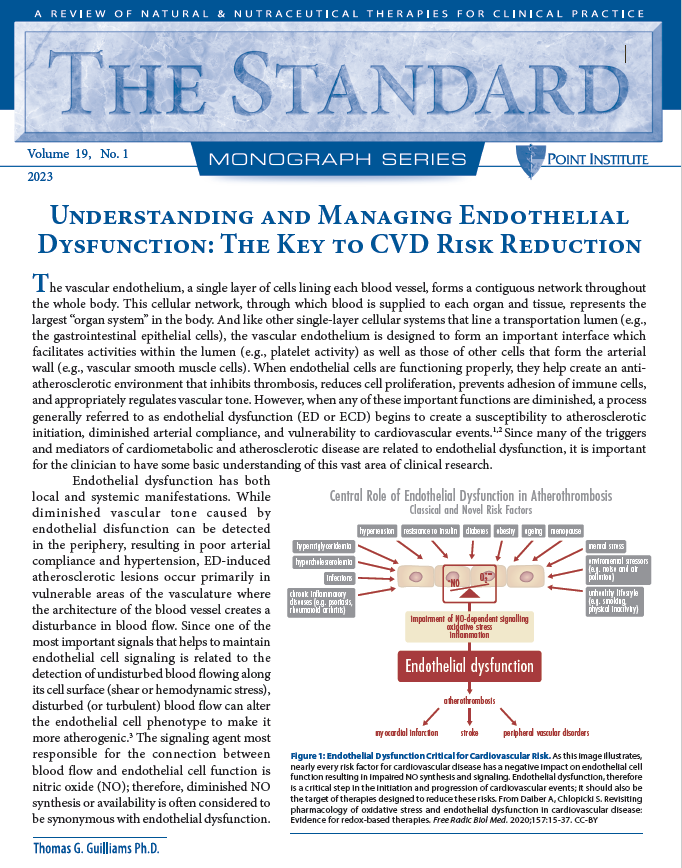

The vascular endothelium, a single layer of cells lining each blood vessel, forms a contiguous network throughout the whole body. This cellular network, through which blood is supplied to each organ and tissue, represents the largest “organ system” in the body. And like other single-layer cellular systems that line a transportation lumen (e.g., the gastrointestinal epithelial cells), the vascular endothelium is designed to form an important interface which facilitates activities within the lumen (e.g., platelet activity) as well as those of other cells that form the arterial wall (e.g., vascular smooth muscle cells). When endothelial cells are functioning properly, they help create an antiatherosclerotic environment that inhibits thrombosis, reduces cell proliferation, prevents adhesion of immune cells, and appropriately regulates vascular tone. However, when any of these important functions are diminished, a process generally referred to as endothelial dysfunction (ED or ECD) begins to create a susceptibility to atherosclerotic initiation, diminished arterial compliance, and vulnerability to cardiovascular events.1,2 Since many of the triggers and mediators of cardiometabolic and atherosclerotic disease are related to endothelial dysfunction, it is important for the clinician to have some basic understanding of this vast area of clinical research.